Listen to this article.

ONE OF THE HARDEST PARTS OF SUPPORTING A FAMILY FACING A PRENATAL DIAGNOSIS OF A LIFE-LIMITING CONDITION IS KNOWING HOW TO COMMUNICATE WITH THEM.

You might be wondering what is helpful or hurtful. You may be worried about saying the wrong thing. You know that you mean well, but you are not sure how your words or actions will be received.

It can be hard to know how to treat your friend or family member who has had this life-changing experience because although they may look like the same person you knew, they are different. Grief changes people at their very core, especially people facing the loss of their baby or babies.

We all expect that, at some point in our lives, we will lose our grandparents, parents, and even to a lesser degree of severity, our pets. These losses are more expected because they follow the natural order of life. Grandparents and parents are older than us, and pets have an average lifespan that is significantly shorter than our own, so we anticipate these losses. Of course, these losses can come too soon, be traumatic, and change our lives forever.

“No one goes into starting a family preparing to bury their baby or babies, and no parent should ever know the pain of outliving their child.”

Pregnancy and infant loss is a different type of loss. No one goes into starting a family preparing to bury their baby or babies, and no parent should ever know the pain of outliving their child. When someone receives a life-limiting prenatal diagnosis, they feel the weight of this loss before they have even had a chance to meet and know their baby. This grief is a nuance of primary and secondary loss.

Primary loss is the initial experience of loss, and in the case of a life-limiting prenatal diagnosis, it is the diagnosis and then the loss of the baby or babies. Secondary loss refers to the losses that emerge as a result of the primary loss. This includes the loss of normalcy, hopes, expectations, and the sense of loss felt at birthdays, holidays, and other important milestones. This ongoing experience of loss lasts a lifetime, and as a member of a family’s support network, it is critical that you understand the importance of remembering this. To read more about the impact your remembering can have, read our post found here.

Since the loss and grief these parents face is so nuanced, it deserves to be handled delicately, particularly when it comes to communicating with them. The words you speak and the way in which you deliver them have tremendous impact on the grieving parents. For parents, the diagnosis, process of carrying to term, and the loss of their baby or babies is an overwhelming experience, and they might feel as though they are aliens in their own life. Struggling to know how to communicate with the world around them and watching those they love struggle to relate to them can feel like loss. They might have difficulty expressing how they are coping and what they need, and the people around them, though they might mean well, sometimes say things that communicate a lack of understanding and empathy.

It can feel isolating when people the parents know well or are barely acquainted with offer clichés and platitudes. There is never going to be a reason that satisfies a parent who lost a baby or babies. Life’s sourest lemons do not make lemonade that quenches a parent’s desire to hold his or her baby again. These parents may find peace and comfort through their own understanding, their faith, or the way they move forward with their life, but it is not up to you to determine what that peace and comfort look like.

Before you offer a cliché or a platitude, take a second to consider your words. Though your intentions might be good, your words come across as insincere. When you are struggling with your own discomfort of not knowing what to say, take a second and put yourself in the parents’ shoes. Form your words from a place of compassion and empathy. If you do not know what to say because you have never been through this tragedy, start with, “I have no idea what this is like for you, but I am here to listen.”

“Please do not be so afraid of causing discomfort or talking about heavy things that you actually end up not supporting the parents at all.”

If you have been through it yourself but do not know what to say, reach out and offer your support and shared experience. Reinforcing the fact that they are not alone, while not dismissing the uniqueness of their own experience, is incredibly powerful.

This may seem intimidating or as though communicating with grieving parents is a minefield. That is okay, and in many ways, you are not wrong. Grief is messy, and supporting someone who is grieving is messy. This is why it is so important to have a solid understanding of empathy and a limitless amount of grace.

If you are reading this and thinking that you would rather just not reach out, I would encourage you to lean into the discomfort. This is not comfortable for anyone involved. Facing the reality that sometimes babies die is hard, whether or not you have experienced it yourself. There is nothing comfortable about a prenatal diagnosis of a life-limiting condition. There is nothing comfortable about losing your baby during pregnancy or shortly after birth. There is nothing comfortable about needing others to care for you, and there is nothing comfortable about learning how to communicate well with someone while in the process of caring for them. So, lean in to the discomfort.

Please do not be so afraid of causing discomfort or talking about heavy things that you actually end up not supporting the parents at all. Instead, reach out, and if you inadvertently say something that is not received well, apologize, learn from it, and do better next time. Your silence is so much louder and more damaging than your sincere and tender attempts to care well for the parents.

Come from a place of empathy and compassion, and do not burden the parents with the weight of your expectations. Let them know that they do not need to respond immediately, attend what you have invited them to, provide you with information they are not ready to give, or cater to your needs. Let them know that you are there for them, genuinely, with no strings.

It may feel as though this is a daunting ask, but in practice, it really is not. It looks like taking your needs and your desire for comfort out of the equation. Acknowledge that you cannot fix what is happening to the parents and offer support anyways. Your words and support do not have to be profound to have impact. Simple words spoken with sincerity speak volumes. Start with sentences like, “I am thinking about you and (baby’s name) today,” “I am always here to listen if you ever want to talk about (baby’s name),” “if you ever want to show me pictures of (baby’s name), I would be honored,” and “I love you, and I am so sorry. I hate this for you.”

“Acknowledge that you cannot fix what is happening to the parents and offer support anyways. Your words and support do not have to be profound to have impact. Simple words spoken with sincerity speak volumes.”

Those words might not feel like much to you, but to the parents, they communicate that you remembered and are willing to support them. If you feel as though you want to do more for a grieving family, there are many practical ways to help. We have a whole post dedicated to helping you support bereaved parents which you can find here.

As the support network coming around a family facing a life-limiting prenatal diagnosis and the loss of their baby or babies, your support is vital. We acknowledge that you cannot understand fully that which you have not experienced for yourself, so we want to empower you to communicate well by providing you with a practical application.

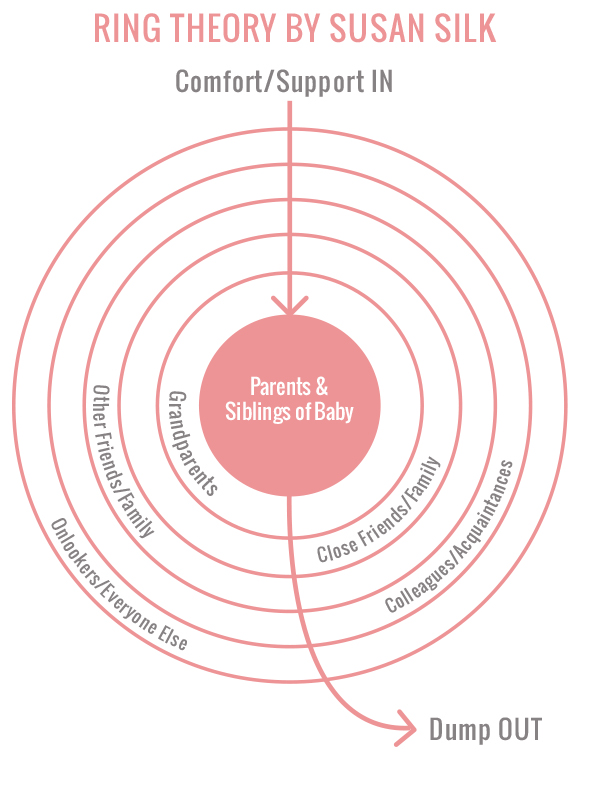

There is a wonderful resource created by Susan Silk called Ring Theory. Susan Silk created it when she was diagnosed with breast cancer, and she realized that some people around her did not understand how to communicate well while respecting her boundaries. The theory is simple, and yet it is something that many people would not think about until trying to communicate with someone facing trauma. I have adapted this theory to fit the specific needs of families facing a prenatal diagnosis of a life-limiting condition, the carrying to term process, and the loss of their baby or babies.

The rules of Ring Theory are simple. Comfort moves inward. Dumping – complaining, wrestling with your feelings, and needing comfort – moves outward. If you are in a larger circle than the person you are talking to, your job is to listen more than you speak. Your sole job is to comfort and validate. When you are in the smaller circle in the conversation, you get to be comforted.

In the center ring, you will find the parents who have received a life-limiting prenatal diagnosis for their baby or babies. The only good part, so to speak, of being in the center ring is that they can complain, cry, grieve, and feel all their feelings with anyone they choose. I would also place any living children of these parents in this same circle. Children need to be able to process with their parents and are free to do so without fear of “dumping in.”

In the next slightly larger ring, you will find the grandparents of the baby. Grandparents have similar freedoms to complain, cry, grieve, and feel all of their feelings like the parents with one very important exception: they do not get to do that to the parents or siblings of the baby. The bereaved parents are to be protected from bearing the burden and weight of their own parents’ grief. There is a difference between grieving with someone and grieving at them. Grandparents, you do not have to hide how you are feeling from the parents of the baby, but if you find that the parents are comforting you more than you are comforting them, you need to find support from someone in your own ring or in a larger ring.

In the third ring, you will find close friends and family members. These are people who are an active part of the parents’ lives. This does not include friends from high school who surface every year to catch up or extended family members who show up to the family reunion every few years.

In the fourth ring, you will find friends and family who are less close but still involved in the lives of the parents. In the fifth ring, you will find colleagues and acquaintances, and in the final ring, you have everyone else. The final ring contains the onlookers, or people who know someone who knows the parents. Unfortunately, in some cases, this ring also contains the busybodies, or people who want to be a part of someone’s story for the attention it brings them.

It is important to know which ring you fall in because it informs the way you communicate with the parents and the other members of their support network. When talking to the center ring or someone in a smaller ring than your own, it is only about them in that moment. It is not about you. It can be about you, your feelings, and your needs when you are talking to someone in your same ring or a ring larger than your own.

“It is important to know which ring you fall in because it informs the way you communicate with the parents and the other members of their support network.”

When talking to the center ring or someone in a smaller ring than your own, do not give unsolicited advice. Do not compare the parents’ experience to the time you or someone you know lost their parent, spouse, friend, or pet. Do not share stories of your sister’s friend’s cousin’s experience. However, it is possible, if you know someone who has been through a similar experience, to offer that as a resource or source of connection and support without dismissing the uniqueness of the parents’ experience.

As the person in the larger ring in the conversation, it is important to not use phrases that start with “at least.” For example, “at least you will get to hold your baby,” “at least you know you can get pregnant,” or “at least your baby will not be in pain.” Empathic communication never uses sentences that start with “at least” because they are dismissive of what the parents’ are feeling.

Put yourself aside and be present for your friend or family member. Sit in the trenches of their suffering with them. Let them feel and speak freely without judgment. Share in their pain and moments of joy with them. Lean into the discomfort, the pain, and the sadness that they are experiencing.

Now, it is, of course, natural to feel the need to cry or talk about the situation and how it is affecting you. If you feel upset or distressed by what is happening, that is natural. If this tragedy happening to someone you know brings up emotions about all the sufferings in your own life, that is okay, too. You are human, and there is nothing wrong with this response to someone else’s experience. What is wrong, however, is putting the responsibility of those feelings and thoughts on anyone in a smaller ring than your own. Find someone in your own ring or a larger ring that you can talk with and process through your feelings.

Ring Theory, at its core, is designed to protect the parents and other members of their support network from being responsible for the feelings and responses of people in larger circles. Honoring the “comfort in, dump out” rule is critical to the well-being of the people in the smallest circles. As you begin to reach the larger circles, the rules are not as black and white. Always be mindful of your ring, and always start from a place of empathy, compassion, and presence.

Being mindful is not the same thing as walking on eggshells. You can reach out to a person in a smaller ring if you are not sure how to care well for them or the center ring. Ring Theory is not about preventing you from talking to or supporting people in smaller rings than you. If you do not know anyone in your same ring or you do not know anyone else in the family’s support network, it is okay to reach out to the parents directly and learn how to best support them. Ring Theory is about protecting the parents’ emotional capacities and honoring their boundaries.

Simply put, communicating with grieving parents starts with having an understanding of empathy. Put yourself in their shoes, consider what this experience must be like for them, and speak with compassion. By communicating this way, you are lessening the isolation that these parents feel. By walking with them without judgment, you are supporting them as they make painful and difficult decisions. By putting your own needs and emotions aside and following the “comfort in, dump out” rule, you are offering a steady and safe place for them to seek support. The way you communicate has a powerful impact, so speak with sincerity, and be mindful of the words you choose.